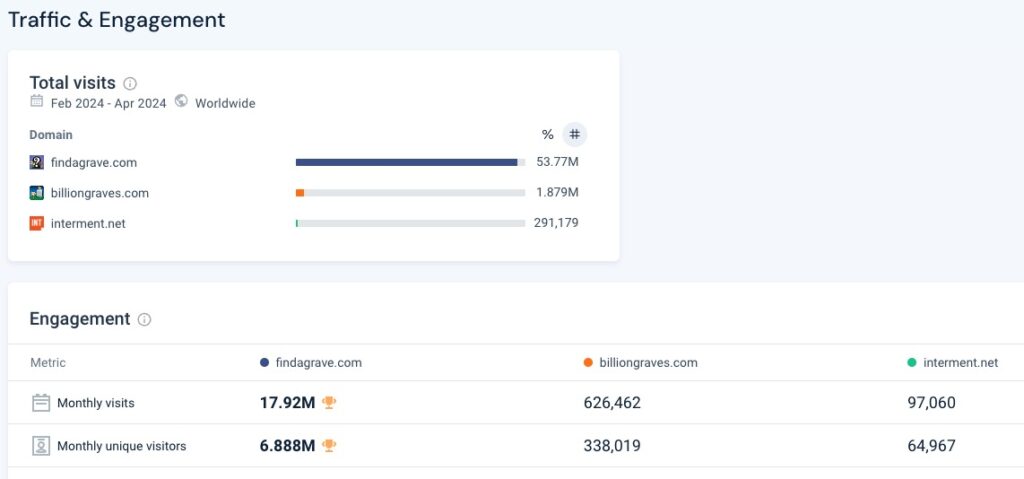

Find a Grave®* has become a popular website for documenting and locating burial information. According to SimilarWeb, it’s the #2 website for the “Community and Society/Decease” category, after Legacy.com, with 6.9 million unique monthly visitors.[1] By comparison, BillionGraves, a similar website, receives only 338,000 unique monthly visitors.

Source: SimilarWeb

238 million memorials have been created at Find a Grave, many of which were duplicates or later deleted, and not all of them document actual gravesites.[2] As of 2020, BillionGraves had 50 million headstone images and 175 million total records,[3] but it’s unclear how many unique graves are recorded. In any case, Find a Grave is much more widely used than BillionGraves. Furthermore, two major genealogy websites have indexes to Find a Grave: Ancestry and FamilySearch. Both of these websites can generate automated hints to possible matches at Find a Grave, which is undoubtedly a reason Find a Grave has so many visitors.

Like Ancestry and FamilySearch family trees, Find a Grave content is user contributed. Unfortunately, Find a Grave is prone to mistakes and even misuse. In this article I’ll offer some best practices for Find a Grave contributors, based on my 12 years as a contributor and user. Although I’ve added only 32 memorials and manage a further 22, I’ve viewed probably over 1,000, based on the fact that I have 930 source citations in my family tree database. So, from a user’s standpoint, I have a pretty good idea of what makes for an ideal memorial.

1. Record only proven deaths, preferably where the final disposition of the remains has been documented. Find a Grave was started by Jim Tipton in 1995 to record the locations of the graves of famous people such as Al Capone and Elvis.[4] Over time, contributors started adding ordinary people, and Tipton told NPR in 2010, “I am sick of drawing the lines of who is famous and who isn’t. I’m just going to accept everyone.”[5] It’s great to record all known gravesites, but at some point, Find a Grave started allowing people to record deaths where the gravesite is unknown. In about 2008, Find a Grave started allowing people who don’t have a traditional grave or tomb, such as cremations or burials at sea, to be added to the site.[6] In these cases, there should still be documentation for the disposition of the remains. But what about people whose date of death or disposition of remains is not known? The urge to memorialize our ancestors is strong, and by Jan 2009, Find a Grave was allowing people buried in unknown locations to be added to the site.[7]

This was a huge mistake, in my opinion, because it allowed people to add any deceased person, regardless of whether there was a known gravesite or even any documentation of the death or disposition of remains. It opened Find a Grave up to all the same problems that exist in people’s family trees resulting from a lack of evidence for their information. As far as I can tell, BillionGraves doesn’t even allow people to be added to their site without a photo of their grave marker.[8] Of course, this eliminates cremations where the ashes aren’t interred somewhere, burials at sea, and unknown burials, but it also reduces the chances for introducing errors based on a lack of sound evidence. While grave markers can contain errors and can become illegible with time, they are at least a form of evidence, and they can be corroborated with other records.

Find a Grave’s mistake in allowing the creation of any type of memorial just means that contributors need to base the memorials they add on sound evidence and reasoning. Grave markers should be the starting point but can and should be supported with burial records, death certificates, obituaries, and similar sources. Which leads to my second best practice…

2. Include all of the sources for the information in the memorial, besides the grave marker. Many grave markers include only the years of death and/or birth, but the memorials give the day and month as well. Or the grave marker includes only a woman’s married name but not her birth surname. Sometimes a marker contains a middle initial but you think you know the middle name (caution: many middle names were added long after the person died!). If you add information to the memorial that’s not on the grave marker or that has become worn away with time, include the source(s). There’s plenty of space in the biography; just add a section called “References” or “Sources” at the bottom. Use any accepted source citation format—Chicago Manual of Style, MLA, Evidence Explained, etc., so that others can find and evaluate the citations. The major family tree applications and websites have tools to create citations. Stand-alone tools like Zotero can create and even store the citations.

3. Add quality images to the memorial that represent the grave marker, the person, or a source. Copyright issues are beyond the scope of this article, but make sure you have the right to add an image to a memorial. Don’t add images of a person that don’t depict the person being memorialized. I once found an image of Frederick V, Elector of the Palatinate, on the memorial for my 8th great grandfather, Jost Riegell, which was completely inappropriate.

Not a 17th-century German peasant! Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt, Frederick V, Elector of the Palatinate (1596-1632), c. 1628-1632, Panel, 37 x 29.5 cm, Kunsthandel Hoogsteder & Hoogsteder, The Hague

There was no citation or explanation for the image; it wasn’t even a very good example of what Jost might have looked like, since he was a common working man, while Frederick V was a nobleman. Just as inappropriate are images of flags, coats of arms that weren’t granted to the person, generic images of ships (denoting an immigrant), flowers, etc. Images like these add nothing to a memorial and detract from the ability of others to add relevant images, since most memorials may have a maximum of 20 photos.

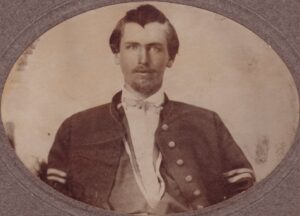

Types of photos that can improve a memorial include high quality, portrait-type photos of the person being memorialized, either singly or with family members. Include the source of the photos along with a description in the caption. Unfortunately, the caption is limited to 250 characters, so while a detailed provenance of the photo would be nice, it’s probably not realistic. Here’s a photo I added of my 2nd great grandfather:

David Milligan Morris, Corporal, Company F, 33rd Illinois Voluntary Infantry. Source: Original owned by Keith Riggle; contact Keith for provenance.

Don’t add family photos that include living people without their permission. Other images to include might be those of important documents, but redact information about living people to protect their privacy, or information on recently deceased people that could be used to steal their identity. Find a Grave has additional guidelines on photos that may or may not be added.

Images of common people before the advent of photography are rare, but here’s an interesting painting I found posted to the memorial of one of my ancestors:

Calvin Lemuel Hoole, “Deputy Surveyor Dutton Lane at John Howard’s Stake, Baltimore County, 1700,” 1858, oil on canvas, 14 x 20 inches.

When I first saw the thumbnail of this image, I thought it was just a generic painting of some Maryland planters, but on checking the caption, I saw that it was a depiction of a story from the life of my ancestor, Dutton Lane. The caption gives the artist and title of the painting but not the source, so I Googled the caption (I could also have done a reverse image search) and found it verbatim in an article at Huffpost, “The Footsore Painter From Missouri, Calvin Lemuel Hoole,” by F. Scott Hess. The lack of a complete citation was probably due to the space limitation, but if the contributor had been more economical with his words, he could have included at least the author, title, and website.

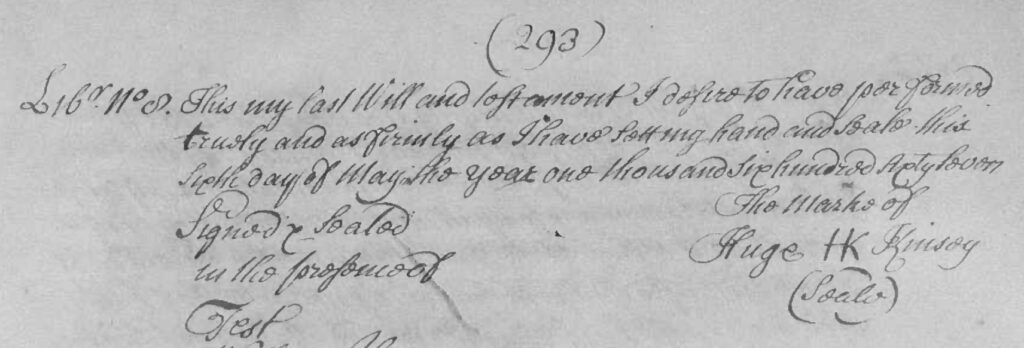

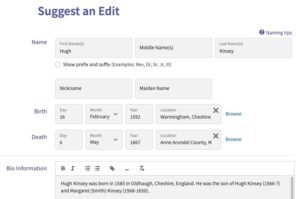

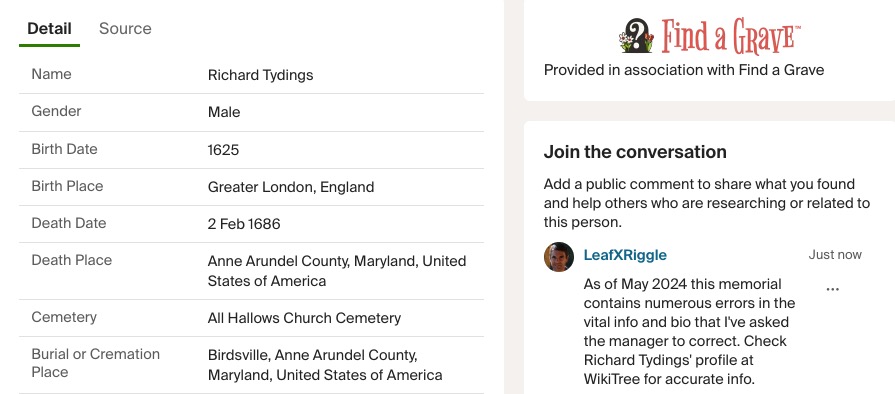

4. Don’t guess at dates, places, or names in the vital info section at the top or the parents or spouse(s) in the Family Members section. Since Find a Grave was intended as a website to record actual graves with information from grave markers, there’s no option to include estimated dates using “about,” “before,” “after,” or “between.” All data in the vital info section should be based on sound evidence such as the grave marker or another reliable record. This is actually the issue that prompted me to write this article. I’ve been working with a lot of people who lived in the 17th and 18th centuries, when vital records were scarce to nonexistent. Instead, there were church and civil records, such as wills or property records. A common source of birth information is the church baptismal record, which sometimes recorded the actual date of birth but often recorded only the baptism date. However, there’s no baptism field on Find a Grave, and there’s no option to state that the birth was before a certain date. Here’s an example: Hughe Kinsie was christened on 16 Feb 1592 under the Julian Calendar, but his Find a Grave memorial states that he was born on this date. This is an error because he was born prior to this date, but Find a Grave doesn’t have a “before” option. Some people might guess that he was born in Feb or Jan 1592, but he could have been born days, months, or even years prior to his christening. The best thing to do is leave the date of birth blank and provide the baptism date in the biography, along with its source.

“England, Cheshire Parish Registers, 1538-2000,” (database, FamilySearch : 10 February 2018), Hughe Kinsie, 16 Feb 1592, Christening; citing item 10, Warmingham, Cheshire, England, Record Office, Chester; FHL microfilm 2,106,690.

Another common problem pertains to using the date of will or probate in lieu of the actual date of death. Wills are signed before death but proved after death. It can take weeks, months, or years for wills to be proved, so there’s no way to know when the death occurred unless it’s explicitly stated in the probate file. Yet I’ve seen memorials using the date the will was signed or proved or something in between, without any evidence of the actual date of death. Poor Hugh Kinsey was a victim of such abuse, with his memorial giving his date of death as 6 May 1667, when he was very much alive and signing his will on that date.

Prerogative Court Records of Colonial Maryland, Wills 1635-1674, Series 538 (digital images, Maryland State Archives, accessed 7 May 2024), liber 1 folio 293, image 293, will of Hugh Kinsey.

In the memorial for Nicholas Dowell, his date of death is given as Jan 1705. When I pointed out to the contributor that his will was signed on 19 Jul 1704 and proved on 9 Aug 1705 and he could have died anytime between those dates, her response was, “The Will would have been written before his death. Usually probating a Will happens close to the death date. I work with Probate Packets, Estates, and Wills.” She does not explain in the biography that Jan 1705 is estimated based on the dates Nicholas’ will was written and proved; it’s just given as if it were a fact, which hundreds of people will blindly copy into their family trees.

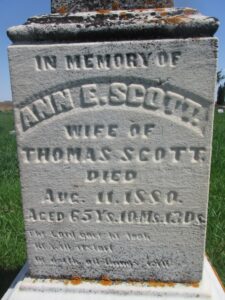

What if information on the grave marker is wrong? Well, presumably you know it’s wrong because there’s a contradictory source. After all, a grave marker is a primary source only for the location of the grave, and even that could be wrong if the marker was moved. Markers are secondary sources for names, date of birth, spouse, marriage, and even date of death. Take the following grave marker of Ann E. Scott:

Photo by Carl Nollen. (Find a Grave, database and images : accessed May 19, 2024), page for Ann E Floyd Scott (28 Sep 1814–11 Aug 1880), memorial ID 84043433, citing Sheridan Cemetery, Sheridan Township, Poweshiek County, Iowa, USA; Maintained by Chris Tonn (contributor 46808630).

It says she died on Aug. 11, 1880, aged 65 Ys. 10 Ms. 13 Ds. Using a date calculator such as the one found in Family Tree Maker, this works out to a birth date of 28 Sep 1814, as stated on the memorial. However, there’s a birth record for Ann stating she was born on 29 Oct 1814, a difference of a month. So either someone’s math was incorrect, or they simply didn’t know Ann’s birth date. The best thing to do is use the actual birth date in the vital info and explain the discrepancy in the biography and/or Gravesite Details, providing the sources.

What about dates other than the Gregorian Calendar? Find a Grave uses only the Gregorian Calendar, for ease of searching. Enter the dates that are inscribed on the grave marker or vital record, or convert them to the Gregorian Calendar (e.g., Quaker dates, but remember that under the Julian Calendar, First Month was March, not January). Then my advice is to use the biography to provide any actual Quaker or double dates or those based on another calendar, such as the Hebrew or Chinese calendar.

Finally, make sure the vital info and biography match. If the vital info says Hugh Kinsey was born on 16 Feb 1592 (ignoring the fact that he wasn’t) in Warmingham, Cheshire, England, then his bio shouldn’t say he was born in 1585 in Oldhaugh, Cheshire. Any time vital info is changed, check the bio to see if it also needs to be changed.

To summarize, if a fact isn’t on the grave marker, don’t put it in the vital info section unless it can be corroborated with reliable evidence. Don’t put guesses or estimates in the vital section—put them in the biography, and explain your reasoning. When in doubt, leave it out—it’s better to leave something blank rather than enter erroneous information. As always, cite your sources.

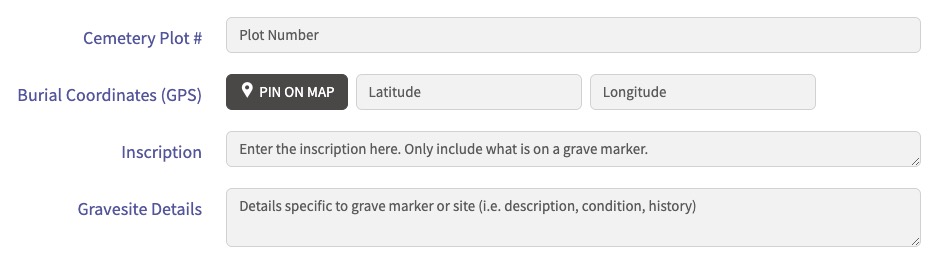

5. Fill in as many other details about the grave as possible. Transcribe the grave marker to the best of your ability and put the transcription in the “Inscription” section, and don’t put anything else there. Copy the inscription just as it is on the marker, with all capitalization and punctuation and even misspellings. If something is illegible, put “[?]” where it goes. Obviously, you can’t include many symbols, but they should be visible in the photo. The Cemetery Plot #, GPS Coordinates, and Gravesite Details can help others find the grave, which is the whole point, after all.

But use these sections only for their intended purpose. For example, on the memorial for Phillip Dowell, the Gravesite Details state, “Phillip Dowell married Mary Tydings on 11 Jun 1702 in Anne Arundel Co., MD.” This is information that belongs in the biography, which I suggested to the memorial maintainer, but she inexplicably refused to move it. Which leads me to my next point.

6. Be open to reasonable suggestions and new evidence. Asking a contributor to move marriage information from the Gravesite Details to the biography is a perfectly logical and reasonable request. But unlike user-contributed family trees such as WikiTree and Geni, only the person who maintains a memorial can change it. Other users can merely suggest changes by clicking the “Suggest Edits” button, which brings up a form where you can enter the changes you think need to be made:

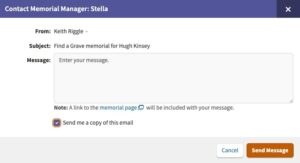

Use the Notes section to explain your rationale for the edits and sources, to include links to websites. Don’t treat this as optional—you can’t expect someone to change their info without a reason. Space is limited here, so if you need more space, click the Contact manager button, which opens an overlaid window where you can type a longer message. I usually use both the Notes and the message because the latter gives the option of sending you a copy of the message, which you can keep as a reminder.

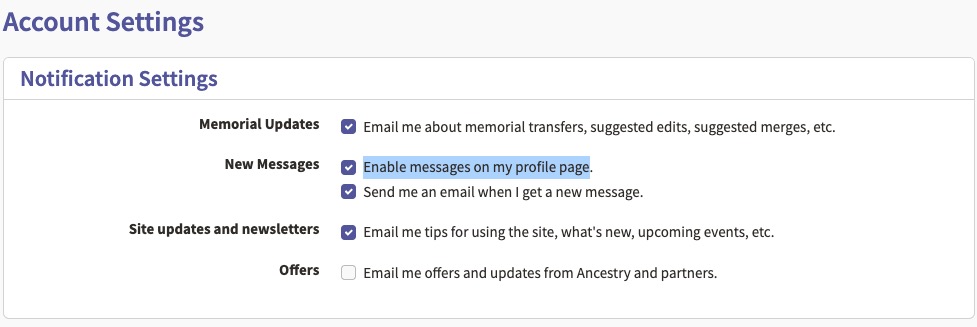

By the way, this is also a way to contact managers who refuse to be contacted; don’t be like them: make sure you “Enable messages on my profile page” in the Account Notification Settings:

I also recommend leaving enabled the boxes for “Email me about memorial transfers, suggested edits, suggested merges” and “Send me an email when I get a new message”. These notifications will help you be a responsive member of the Find a Grave community and can be especially important for suggested edits. If you don’t respond to suggested edits in 21 days, they’re automatically queued for processing.

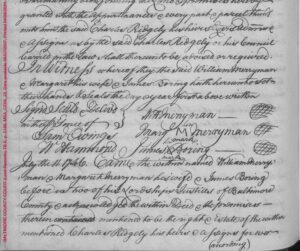

When you receive suggested edits, have an open mind: what reasons and sources does the suggester provide? Is their evidence weightier and/or more reliable than the evidence on which your information is based? For example, there was a memorial for a Margaret Merryman where the date of death was given as 1742, presumably based on someone’s family history, because the burial location wasn’t even known, so there was no grave marker. There were no known death or burial records, and Margaret was a woman who predeceased her husband, so there was no will or estate to probate. In an effort to find some evidence of when Margaret died, I searched the property records for where she lived, Baltimore County, Maryland, and found a property deed that she signed along with her husband, William, in 1746:

Maryland State Archives (online database and digital images, accessed 15 May 2024), Baltimore County Court, ”Land Records 1745-1747” Liber TB E, folio 166, William & Margarett Merryman & James Boring to Charles Ridgely.

We can see that Will Merryman signed this deed, Marg Merryman signed with “her M mark,” and James Boring signed with “his mark.” When I sent this deed to the memorial manager, they said that William must have signed for Margaret because she was already dead! I pointed out that if she were dead, the deed would have referred to her as “Margaret Merryman, deceased” and/or “late of Baltimore County,” and William would have been referred to as her administrator or executor. The manager still refused to remove the erroneous date, stating that the 1742 date would stand until Margaret’s exact date of death was determined, ignoring the fact that 1742 wasn’t an exact date, either. So I had to be content with uploading a copy of the deed to the memorial and explaining in the caption how she was still alive in 1746.

But then I found another deed, this one from 1750. Margaret didn’t sign this one; instead, she appeared before two justices of the peace for Baltimore County regarding the sale of a tract of land called “Merrymans Grotto.” According to the deed of sale, “And at the same Time came Margeret Merryman wife of the said Wm. Merryman who being parted and privately examined out of the hearing of her husband did consent that her consent was volontary [sic] and without constrant [sic] of her husband”[9] I uploaded this deed and again asked the manager to blank out Margaret’s date of death. I guess they couldn’t argue that Margaret was already dead this time because they made the change, and not only that, they transferred the memorial to me for management without asking! I didn’t object, but best practice would be to ask first before transferring a memorial to another person. They might not want the responsibility for maintaining another memorial, which I’ll discuss under best practice #7 below.

After weighing the evidence that a suggester sends regarding a proposed change against the evidence you already have, if you conclude the current information is correct, don’t just decline the edit without an explanation. I’ve lost track of the number of times my edits were declined with the statement, “Suggestion does not match information I have for this person or memorial,” which is a canned reason Find a Grave offers for declining an edit. Show some good will, humility, and professionalism and provide your rationale and sources. Since Find a Grave is a collaborative effort, members should treat each other with respect and try to get along the way they do with any other team.[10]

What if your edits are declined but you still believe they’re correct, despite whatever explanation the manager provides? Unfortunately, there isn’t much you can do. Find a Grave guidelines are to submit requested edits no more than twice, at least once with a note with supporting information. Before I finally convinced the manager of Margaret Merryman’s memorial to delete her date of death, I sent a request to Find a Grave Support about what I could do. In her response to me, Marie, Sr. Find a Grave Administrator, reiterated the process for submitting edits but concluded, “If you’ve sent your suggested edit twice and both have been declined, Find a Grave will respect the manager’s decision as they are responsible for information on the memorial.”[11] In my query to Find a Grave, I had pointed out how widely used Find a Grave is and how their information gets propagated throughout people’s family trees, due partly to their ties with Ancestry and FamilySearch. But it appears that Find a Grave is less concerned with the accuracy of information in memorials than they are with driving traffic to their parent and sister sites, Ancestry, Fold3, and Newspapers.com.

Find a Grave with ads for parent and sister sites

However, you’re not completely without options. First and foremost, upload your evidence to the memorial and explain in the caption how it contradicts information on the memorial. You could also use the Flowers feature on a memorial to add a comment explaining the error.

I try not to do this, since it might be in a gray area. Find a Grave doesn’t state what Flowers are for—it’s just assumed. They do state, “Do not leave derogatory, politically charged, biographical information, or obituaries as a note.”[12] One last thing I do is add a note about the error in my family tree, as well as the corresponding profiles on collaborative family trees at Family Search Family Tree, Geni, and/or WikiTree. Here’s an example at WikiTree:

You could also leave a comment on the record in the U.S., Find a Grave Index at Ancestry:

7. Have a succession plan. None of us is going to live forever, so we need to have a plan for our digital assets just as we do for our physical assets. Although we don’t own our Find a Grave memorials, as managers, we’re the only ones who can edit them, except for Find a Grave itself, and they have a small staff to process a large backlog of support requests. I suspect that the age of Find a Grave managers tends to skew older, just as it does with genealogy and family history overall. An Australian study found the median age to be 62.[13] Older, retired people have the time and interest to walk cemeteries and create memorials for Find a Grave and similar sites. What’s doing to happen to all those memorials as their managers die? Just as actual graves can fall into disrepair without care, will Find a Grave memorials simply be abandoned? I’ve already run across a few where the managers were nonresponsive. Fortunately, after 21 days without a response, Find a Grave approves edits automatically. But there’s more to managing a memorial than responding to edits, such as responding to messages from other users.

Find a Grave actually has a process for appointing successors to managers; they call the successor a steward. You find someone to take over your memorials if you can no longer manage them. Obviously, you’ll need to speak to the potential steward and get their agreement, and they’ll need to have a Find a Grave account of their own. This may be easier said than done. In my case, I manage memorials for both my wife’s side of the family, as well as my own. The only people remotely likely to be interested are my children, and so far I haven’t succeeded in interesting them in family history. But assuming I can get one of them to take over my account when I die, I just need to send their Find a Grave member number to support@findagrave.com. Once a contributor becomes inactive, Find a Grave will take over management of their memorials. I sure hope they have a plan for taking over millions of memorials![14]

Find a Grave can be an excellent source of genealogical information, but the quality of that information is only as good as the evidence it’s based on. Recording the details of our relatives’ and ancestors’ lives is a serious matter, and we owe it to their families to ensure memorials are as accurate as possible. By following the seven best practices in this article, contributors can help provide high quality memorials that stand the test of time, even after we ourselves have become the subjects of memorials.

*“Find a Grave” is a registered trademark and service mark of Ancestry.com Operations Inc. of Lehi, Utah.[15]

References

- “Website Performance.” (SimilarWeb, Accessed 17 May 2024).

- “Millions of Cemetery Records.” (Find a Grave, accessed 17 May 2024).

- Wallace, Cathy. “What Is the Difference Between BillionGraves and Find A Grave for Researchers?” BillionGraves Blog, 6 May 2024. Accessed 17 May 2024.

- “Episode 13: Jim Tipton Founder of Find-A-Grave”. Extreme Genes. 2013. Archived from the original on 12 Aug 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- Silverman, Lauren (March 14, 2010). “Tracking Down Relatives, Visiting Graves Virtually”. Washington, D.C.: National Public Radio. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- “Find a Grave Frequently Asked Questions: What if someone was cremated or does not have a traditional ‘grave’?” Find a Grave. Archived from the original on 4 Jan 2008. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- “Find a Grave Frequently Asked Questions: How do I add a memorial when I’m not sure what cemetery they are buried?” Find a Grave. Archived from the original on 29 Jan 2009. Retrieved on 18 May 2024.

- “Step 1: Get the app.” BillionGraves. Accessed 18 May 2024.

- Maryland State Archives (online database and digital images, accessed 9 May 2024), Baltimore County Court, Land Records 1750-1753 Liber TR D, folio 14-16, William Merryman with consent of Margeret Merryman to Jabus Murray.

- “Suggest Edits and Community Interaction.” Find a Grave, accessed 20 May 2024.

- Marie, Sr. Find a Grave Administrator, support@findagrave.com, to Keith Riggle, e-mail, 16 May 2024, “Find a Grave Contact: Account Question.”

- “Questions about Flowers: What may not be included as a Note on a Flower?” Find a Grave, accessed 21 May 2024.

- Moore, Susan M., and Doreen A. Rosenthal. 2021. “What Motivates Family Historians? A Pilot Scale to Measure Psychosocial Drivers of Research into Personal Ancestry” Genealogy 5, no. 3: 83.

- “Management Questions: How do I add a Steward to my account?.” Find a Grave, accessed 20 May 2024.

- USPTO. “Trademark Search” (online database, accessed 21 May 2024), entry for “Find a Grave,” US Serial Number 86339891.

Leave a Reply